The brain’s ability to preserve memories lies at the heart of our basic human experience. But what is its mechanism to make sure we remember the most significant events and keep our minds free of superfluous details?

According to a new study by Columbia University researchers, the brain plays back and prioritizes high-reward events for later retrieval and filters out the neutral, inconsequential events, retaining only memories that are useful to future decisions.

Published on November 20 in the journal Nature Communications, the findings offer new insights into the mechanisms of both memory and decision making.

For memories to be most useful for future decisions, we need them to be shaped by what matters, and it’s important that this shaping of memory happen before choices are made.

“Our memory is not an accurate snapshot of our experiences. We can’t remember everything,” said Daphna Shohamy, PhD, senior study author and principal investigator at Columbia's Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute and a professor in the Department of Psychology. “One way the brain solves this problem is by automatically filtering our experiences, preserving memories of important information and allowing the rest to fade.”

The effect, however, is not immediate. “The prioritization of rewarding memories requires time for consolidation,” said study co-author Erin Kendall Braun, who conducted this research as part of her doctoral work in the Shohamy lab at the Zuckerman Institute and in psychology at Columbia’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “Our findings suggest that the window of time immediately following the receipt of the reward — as well as a longer overnight window including sleep — work jointly to modulate the sequence of events and shape memory.”

To carry out their study, the researchers asked participants to explore a series of computer-simulated mazes looking for a hidden gold coin, for which they were paid one dollar. The maze was made up of a grid of grey squares, and as participants navigated it they were shown pictures of everyday objects, such as an umbrella or a mug. The researchers surprised participants with a test of their memory for these objects immediately afterwards.

When the memory test was given 24 hours later, participants remembered the objects closest to the reward (the gold coin) but not the others. This suggests the reward had a retroactive effect; memory for objects that had no special significance when initially seen were later recalled only because of their proximity to the reward. To the researchers’ surprise, this pattern was not found when they tested memory immediately. The brain needed time to prioritize memory for the events that led to the reward.

The test was replicated six times in different variations with a total of 174 participants, with similar results.

“The experiment demonstrates that what gets remembered isn’t random, and that the brain has mechanisms to automatically preserve memories important for future behavior,” said Dr. Shohamy. “For memories to be most useful for future decisions, we need them to be shaped by what matters, and it’s important that this shaping of memory happen before choices are made.”

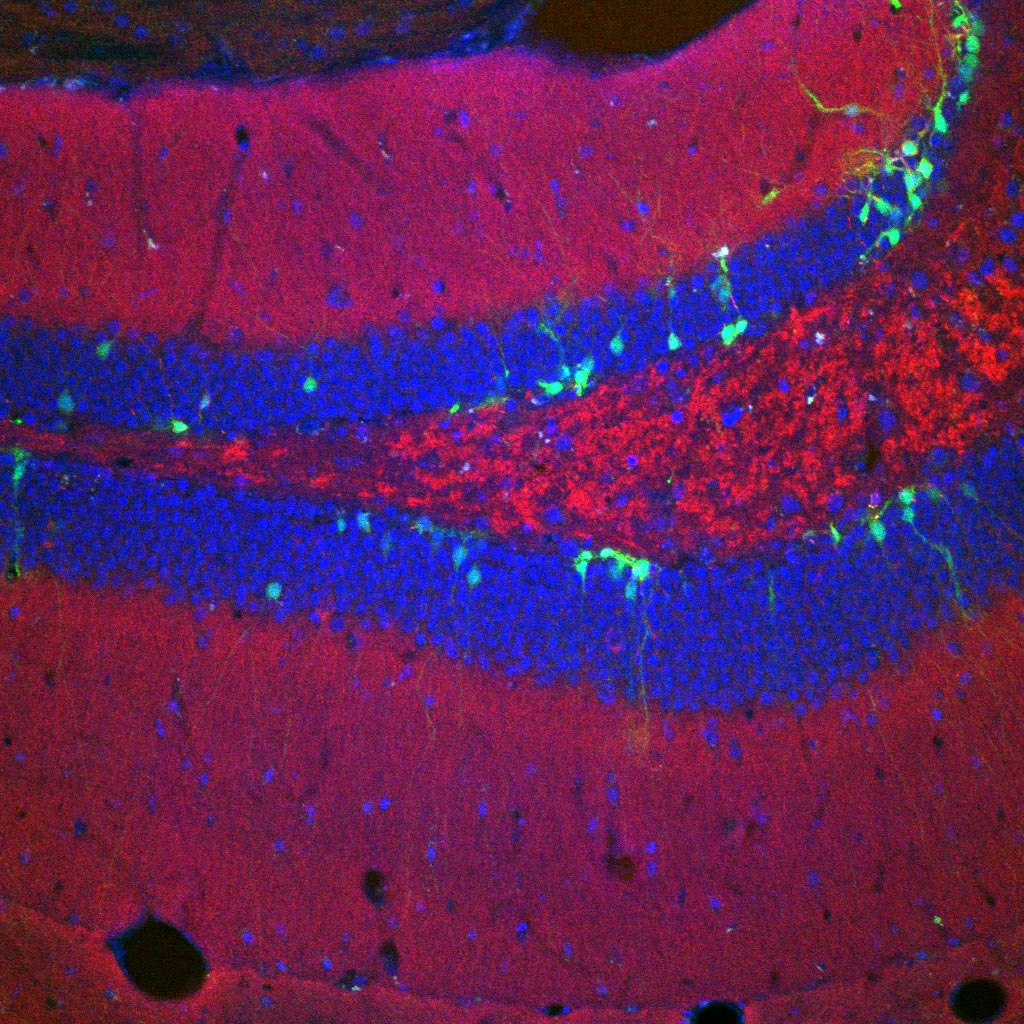

Though the data provide insight into the structure of memory playback, how this happens in the human brain remains a mystery. The process probably involves dopamine, a chemical known to be important for signaling rewards, and the hippocampus, the brain region associated with long-term memory. Further research is needed to understand the mechanism by which this occurs.

An important follow-up question would be the effect of negative events on memory, a study “that would be a lot less fun for the participants,” said Dr. Shohamy. But like the current study, “it would help us understand how motivation affects memory and decision making. This understanding would have important implications for education and also for mental health.”

###

By Carla Cantor. This article first appeared on Columbia News.

This paper is titled “Retroactive and Graded Prioritization of Memory by Reward.”

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health (5R01DA038891), the McKnight Foundation (MCKNGT CU16-0460) and the National Science Foundation (Career Award BCS-0955494; Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1144155).