In a scientific first, researchers have observed in mice how the brain learns to repeat patterns of neural activity that elicit the all-important feel-good sensation. Until today, the brain mechanisms that guide this type of learning had not been measured directly.

This research offers key insights into how brain activity is shaped and refined as animals learn to repeat behaviors that evoke a feeling of pleasure. The findings also point to new strategies for targeting disorders characterized by abnormal repetitive behaviors, such as addiction and obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD.

The study, led by researchers at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute, the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown and the University of California at Berkeley (UC Berkeley), was published today in Science.

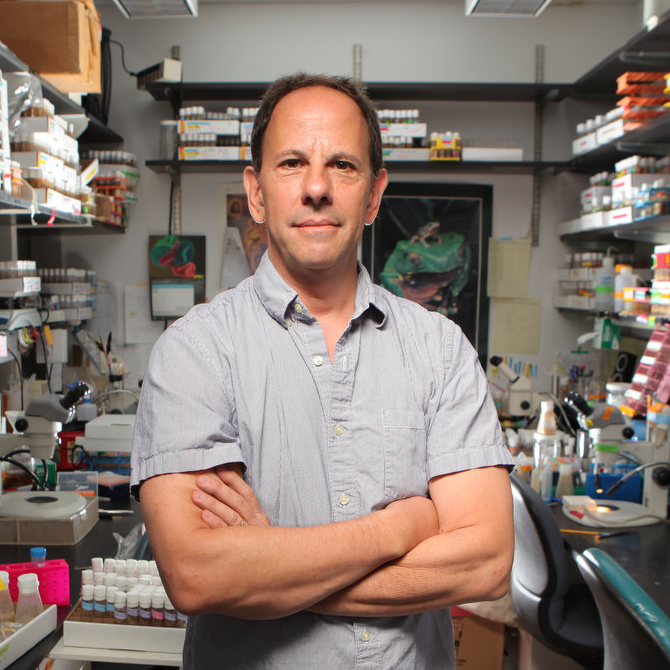

“It’s no secret that we derive pleasure from doing things we enjoy, such as playing our favorite video game,” said Rui Costa, DVM, PhD, senior author and the associate director and CEO of Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute. “These results reveal that the brain learns which activity patterns lead to feel-good sensations, and reshapes itself to more efficiently reproduce those patterns.”

If a brain’s activity patterns are in overdrive, as is often the case for people with addiction or OCD, could we create a computer program that can help to retrain their brains and downshift this activity?

“In our previous studies, we developed a brain-machine paradigm showing how neural-activity patterns that lead to reward are repeated more often and become consolidated over time,” said Jose Carmena, PhD, professor of electrical engineering and neuroscience at UC Berkeley and the other senior author of the paper. "That research provided a framework for how those patterns of activity could be driving learning in the brain.”

“Today’s discovery in mice builds on that foundational work; it can help explain how we learn by repetition, and can also inform studies of disorders such as addiction and OCD, in which the feedback loop that links an action to a reward gets thrown out of whack,” added Dr. Costa.

Normally, doing something enjoyable triggers neurons, a type of brain cell, to release a chemical called dopamine. This release causes that feel-good sensation, evoking the desire to repeat an action again and again. Video games are prime examples of this.

“When you move the game controller in exactly the right way to earn that high score, your brain remembers how it executed that action — which neurons get switched on, and in what pattern — so your brain can recreate that same move the next time you play,” said Dr. Costa, who also a professor of neuroscience and neurology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “After repeated attempts, your brain gets better at recreating that pattern of neural activity, and you get better at the game.”

To the team, this fact then begged the question: Could the brain be trained to learn the right pattern of neural activity normally involved in experiencing something enjoyable, and then replay that pattern at will to trigger a dopamine release?

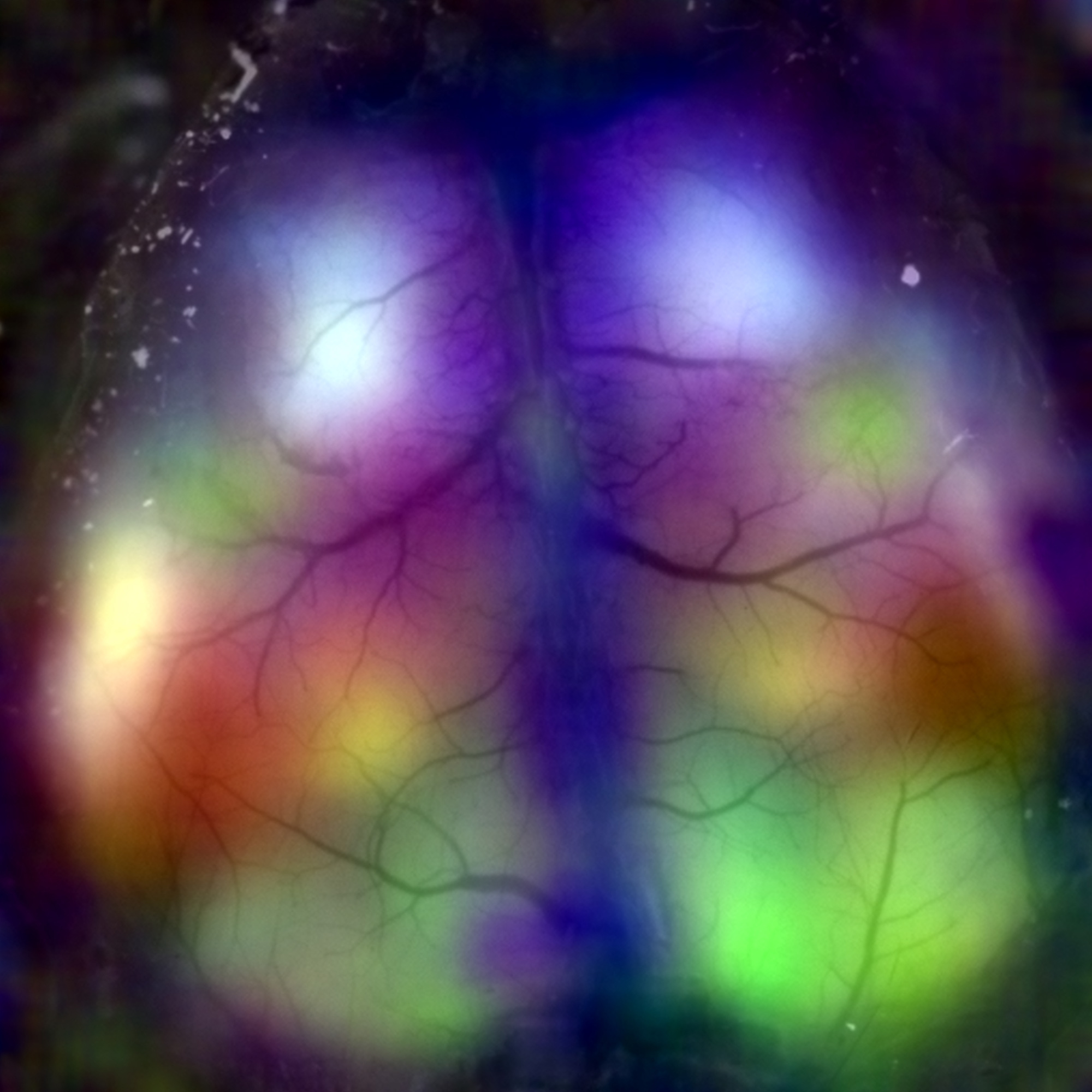

In a series of experiments in mice, the researchers developed a computer program that connected the neural activity in the animals’ brains to musical notes, so that when one group of neurons switched on, a corresponding musical note played. Different patterns of neural activity yielded different combinations of notes. And when neural-activity patterns triggered the right arrangement of musical notes (arbitrarily determined by a computer), the scientists manually released dopamine in the animals’ brains.

The mice quickly learned which musical arrangement that, when played, caused a dopamine release and the feel-good sensation. Their brains then began to rewire themselves to play that song more often, thereby triggering the pleasure hit of dopamine.

“In essence, the mice learned to repeat the same pattern of brain activity that had been evoked previously by hearing those musical notes,” said Vivek Athalye, a doctoral candidate at UC Berkeley and the paper’s co-first author.

The researchers noted that these findings are a striking example of Thorndike’s Law — a long-held principle of psychology stating that actions that lead to positive reinforcement are repeated more frequently. However, these findings likely represent the first time that this principle has been directly observed in the brain.

“In some ways, these results are entirely expected,” said Dr. Costa. “It makes sense that the brain would mimic the feeling of reward it gets from an enjoyable experience by producing the corresponding pattern of neural activity. But it had never been tested.”

“This research also has important implications for the development of advanced neurotherapies, systems that would treat the underlying causes of brain disorders by modifying a patient’s neural-activity patterns,” said Dr. Carmena.

“For example, if a brain’s activity patterns are in overdrive, as is often the case for people with addiction or OCD, could we create a computer program that can help to retrain their brains and downshift this activity?” asked Dr. Costa. “This is something we’re actively exploring.”

###

This paper is titled: “Evidence for a neural law of effect.” Additional contributors include co-first author Ferndando Santos.

This research was supported by National Science Foundation (Graduate Research Fellowship, CBET-0954243, EFRI-M3C 1137267), Office of Naval Research (N00014-15-1-2312, ERA-NET, European Research Council (COG 617142) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (IEC 55007415).

The authors report no financial or other conflicts of interest.