As a high school freshman, Ishmail Abdus-Saboor turned the top floor of his family’s home in Philadelphia into a biology lab, and ran experiments on crayfish to see if ginseng would boost their reproduction rates. For an entire year the house reeked of fish, but Abdus-Saboor’s science project made it to the statewide finals and pointed him to his life’s work.

“I realized then I was going to be a scientist one day,” he said.

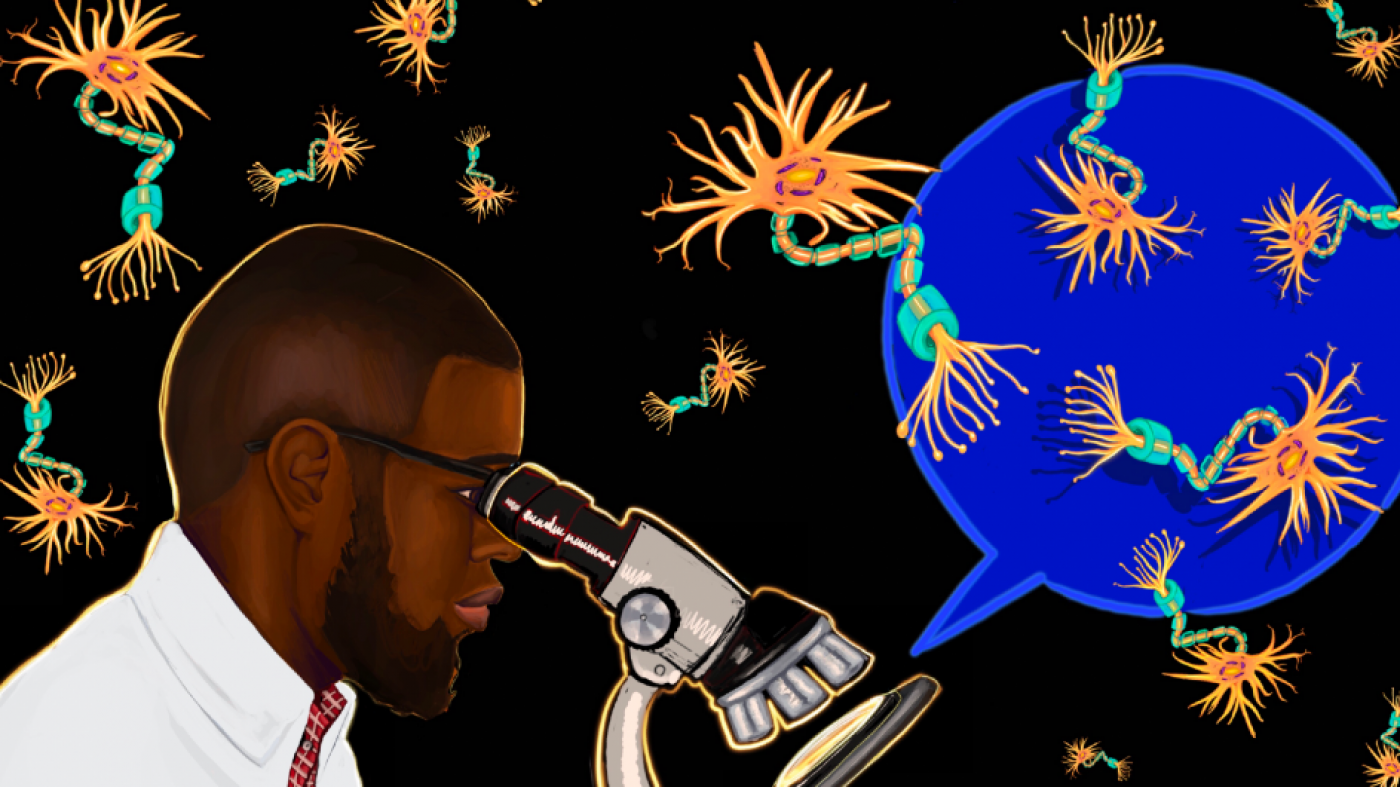

Two decades later, Abdus-Saboor is an assistant professor of biological sciences at Columbia, leading a 12-person lab at the university’s Zuckerman Institute. He studies how the sense of touch gives rise to pleasure and pain in rodents which include, as of several months ago, naked mole rats. The work is part of a larger effort to understand chronic pain and develop more objective ways of measuring discomfort.

In a recent study in Science Advances, Abdus-Saboor found that rats with long-term opioid use passed down a tolerance to the drug to their offspring. “This study suggests that parental opioid use might be something we should consider when treating patients with opioids,” he said.

The oldest of six children, Abdus-Saboor followed his parents, an accountant and an actuary, to a historically Black college and university (HBCU)—North Carolina A&T State University. He arrived at Columbia last year, mid-pandemic, after postdoctoral work at University of Pennsylvania (where he earned his PhD), and Weill Cornell Medicine. In a recent interview, Columbia News chatted with Abdus-Saboor about his experience as a Black scientist, his work with naked mole rats, and why science needs more outsiders.

Q. A queen naked mole rat and her colony recently joined your lab. What makes this animal so interesting?

A. Naked mole rats evolved in East Africa and live an extreme lifestyle completely underground. They are essentially blind, but compensate with whisker-like vibrissa throughout their skin, and giant, externally placed incisors that they use like hands. They live 30 years or more, making them the longest lived of all rodents. They show no signs of aging, are resistant to cancer and some forms of pain, and can go long periods without oxygen. Like bees and ants, they’re eusocial, living in colonies of dozens to hundreds of animals within a caste system. We want to understand the neurobiological basis of their insensitivity to pain, and behaviors tied to their hierarchical social structure.

Q. Pain tells most animals when to back off from danger. How have naked mole rats managed to survive?

A. They probably evolved their insensitivity to pain by adapting to a highly social and cooperative lifestyle underground. Since they don’t have an army of predators underground, they could probably lose their sensing of some forms of pain with little consequence.

Q. What has your lab learned so far?

A. Using our high-speed video-imaging system, we’ve identified naked mole rats that fail to respond normally to mechanical stimuli applied to their skin. We’re currently investigating further.

Q. Why is pain interesting to neuroscientists?

A. Chronic pain is a major burden for many people. The inability to properly treat it, some of which can be tied to a lack of understanding of the neurobiology of pain from skin to brain, lies at the heart of the current opioid epidemic. Many people with chronic pain face a shortage of options. Opioids have become a mainstay, despite their potential for abuse and their failure to treat many forms of chronic pain.

We need all voices at the table for us to reach our full potential.

Q. How did your undergraduate years at an HBCU shape your career?

A. My parents attended Howard University, and so did many of my relatives. I followed in their footsteps, and that was really important in my development. I got to meet Black scientists and medical doctors for the first time. I also had Black peers, and we supported each other instead of competing with one another. We had professors who loved you, believed in you, and thought, ‘Sure, this Black kid could be the smartest person in the class.’

Q. What’s the biggest challenge you’ve had to overcome?

A. In college I thought I wanted to become a veterinarian, in hindsight, because I didn’t know any scientists growing up, and I didn’t know what a career in science looked like. So, I thought, ‘You like animals, you should become a veterinarian.’ But midway through college I realized I didn’t like veterinary medicine, so I was left with a conundrum. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. Fortunately, through an internship at Penn, in a program geared towards underrepresented minority scientists, I got to work in a molecular biology lab and fell in love with working at the bench on big problems.

Q. How have you navigated a field that’s overwhelmingly white?

A. Feeling like an outsider is an ongoing struggle as a Black scientist. I’ve worked hard to form community with peers so that I’m not an only in my environments. But feeling like an outsider at times benefits my science, because I’m not afraid to break away from the crowd to solve problems.

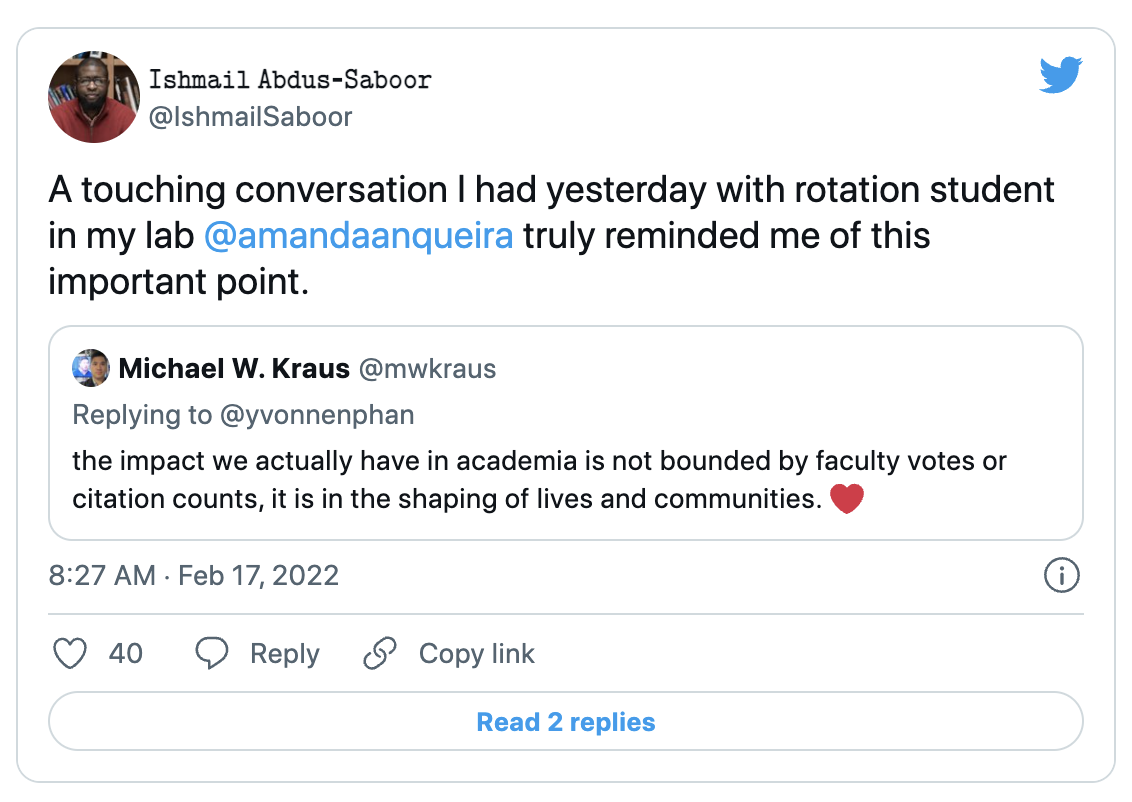

Q. You’ve built a large and active following on Twitter. Can you sum up your philosophy in a tweet?

A. Stay connected to updates from colleagues in somatosensory neurobiology, and neuroscience and biomedicine more broadly. Lift up voices in science that have historically been undercelebrated.

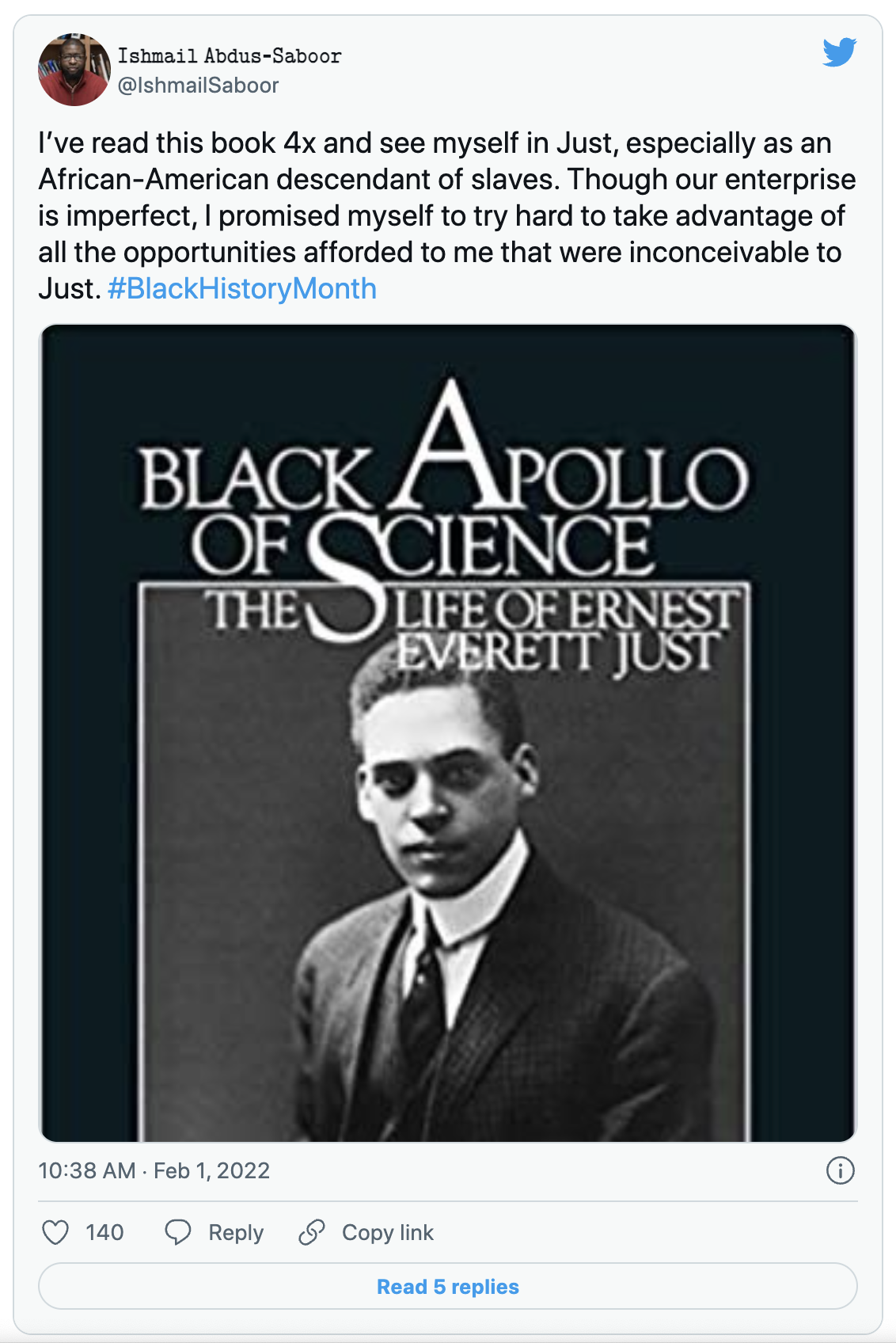

Q. Here’s another excerpt from your Twitter feed. Who was Ernest Everett Just?

A. He was a pioneering developmental biologist. The only reason he’s not remembered as one of the greatest biologists of the 20th century is because he was denied access and resources, only because of the color of his skin.

Q. You spend a lot of time mentoring students. Why is that important?

A. Too often the signals we give to our students are that they’re not good enough, and that they don’t belong. Through mentoring, I directly counteract that by telling Black scientists in particular, ‘We need you: we need your voices, we need the questions that you bring that are important for your community. We need the different ways that you go about solving big problems.’ We need all voices at the table for us to reach our full potential.

Q. Advice for aspiring Black scientists?

A. Dream for the stars, reach for the stars. We need you. Don’t self-select yourself out of this career because you feel that it’s too difficult or you don’t see enough people who look like you. Go for it!

This story was originally published by Columbia News